|

Only The Sunny Hours photo album Marco Calí, Wim Daems, Alex Dewart, Peter Driver, Barbara Dyrschka, Linda Francis, Judy Goldhill, Jane Grisewood, Hepzibah Hill, Ingrid Jensen, Lydia Julien, Philip Lee, Sophie Loss, John McDowall, Steve Perfect / Jennifer Partridge, Roger Perkins, Ann Rapstoff, Guy Tarrant, Roxana Tohaneanu-Shields, Cally Trench, and Nick Trench. |

|

Only The Sunny Hours Invited artists used Kodak Brownie 127 cameras manufactured between 1952 and 1963 to take photographs. The project was an exploration of how the artists decide to use this sixty-year-old technology and the impact of the technology on the artists. Some of the artists were influenced by the age of the camera to explore their own history, or the history of the camera and its previous owners, or of the area where they live or have lived. Others recorded technology, poses and behaviour that are clearly contemporary. Some of the artists attempted to take the kind of photographs that they would take with a contemporary digital camera. Only The Sunny Hours: Contemporary Photography with a Brownie 127 was exhibited at Openhand Openspace, Reading, 20th-24th June 2018, with an Open Day on Saturday 23 June, 12 noon - 6pm, including performances, short films, talks, discussions and readings by the artists, plus a Brownie 127 studio and an Indoor Picnic. Curator Cally Trench: Just to handle one of these 50-year-old black bakelite boxes takes us back in time - to when it was used by a younger self or an older relative. They are so familiar to us, having been so ubiquitous. The Kodak Brownie 127 camera, like a sundial, works best in bright sunlight. Sundials usually have mottoes; a typical one is 'I tell only the sunny hours', and this would be a good motto for a Brownie 127 too. According to my family photograph album, my childhood was a series of sunny days by the seaside or in the garden. We spent no time indoors, and there was no winter and no night. Many of these photographs show relatives lined up in the garden, but my grandmother also had a taste for dressing me up - as a nurse or in a grass skirt. Everyone looks directly at the camera, warned and fully aware that they are to be photographed, their expressions composed, eyes fixed open, waiting for the button to click. In these digital times, using an analogue camera, especially one as unsophisticated as a Brownie 127, requires a change of thinking. Processes such as loading the film, pressing the shutter button and winding on, once so easy, necessitate an unfamiliar manual dexterity and care. Immense forethought and planning, combined with a kind of letting go, are demanded by the limits of the camera: only eight exposures on a film; fixed focus, depth of field and shutter speed; no flash, tripod attachment or stabiliser function; and a viewfinder that does not correspond accurately with the lens. And then the film is posted to the processor, and the waiting begins. Roland Barthes argued in 1980 in Camera Lucida that 'a photograph is always invisible'; what we see is always the person or place or object photographed, not the photograph itself. But when these Brownie 127 photographs return from the processor, what we first notice is how photograph-like they are, how unlike digital images on a screen. The negatives and the prints are physical objects, which we can hold in our hands. Beyond that, the photographs are redolent of the 1950s and 60s - not just black and white, and of a different proportion to digital images, but also, as Judy Goldhill describes it, with 'such strange, soft focus and distortion'. In a kind of reversal, we notice firstly the photograph and secondly its content. In these efficient times, where cars rarely break down, word processing has ironed out the idiosyncrasies of typewriters, and digital cameras take perfect images in all conditions, old photographs have acquired an allure of authenticity and uniqueness. In a nostalgic attempt to recapture some of that value, advertising agents and others use digital cameras and apps on phones to produce old-appearing photographs - a phenomenon that Nathan Jurgenson described in 2011 as 'faux-vintage' in 'The Faux-Vintage Photo' - by replicating a shallow depth of field, adding scratches, etc. How, if at all, can photographs taken recently with real 127 film on real Brownie cameras be distinguished from the faux-vintage, especially as the 127 photographs have to be scanned and made digital anyway in order to be shown on this website? Does it matter that the photographs in this project were taken on a Brownie 127? Photography, more than any art form, often seems to need a context, a title, an explication. We want to know who, when and where. We are unwilling to accept a photograph as universal. It matters if the location is Glyndebourne or Strood, whether the sitter is Napoleon's younger brother in 1856 (the photograph with which Barthes opens Camera Lucida), or myself as a child in 1962. So, yes, it is significant that these photographs were taken with simple vintage cameras using film, because these things affect not just the photographs that are made but also how they are received by viewers. Many writers have tried to identify the unique character of photographs, arguing that they are about the moment, or death, or time, that they are ubiquitous or unique, truthful or unreliable, elitist or democratic, public or private. Photographs seem, maybe because of the relatively recent technology of photography (although film feels so weighted with history now), to engender this kind of debate more than other kinds of 'pictures', such as paintings, prints or drawings. Could we not, however, simply consider each photograph in its own right as a picture, whose form is inherent, because what surely matters in the end is whether we give any picture a second or third glance, whether it sticks in our heads, whether it alters in some microscopic degree how we think about the world? |

Brownie 127 Model I |

Brownie 127 Model I |

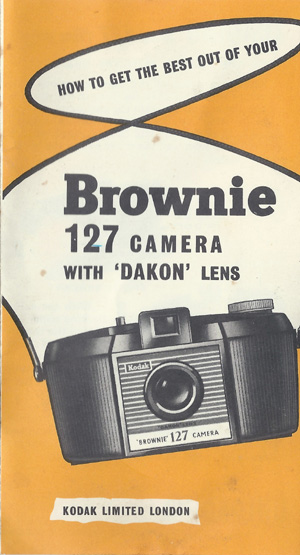

Leaflet for Brownie 127 |

|

Brownie 127 cameras The Brownie 127 camera is both unsophisticated and clever. It has a fixed shutter speed, fixed focus (so anything closer than five feet away is out of focus), fixed depth of field, no flash, and no tripod attachment. The 127 film, which has lightproof backing paper, is loaded in a darkened room (or you can, according to the loading instructions,'take the camera into the shade'). You must wind on by hand, and numbers on the outside of the lightproof backing paper show through a small red window in the back of the camera to tell you when to stop. Brownie 127 cameras were made in their millions by Kodak from 1952. The first model exists in two variants. The first, made from 1952 to1955, can be identified by the plain faceplate surrounding the lens. The second, made from 1956-1959, has a cross-hatched faceplate. The camera had a Meniscus f/14, 65mm lens, and a single shutter speed of 1/50 second. The second model, with horizontal stripes on the faceplate and vertical ribbing on the body, was made between 1959 and 1963; it has a Dakon f/11 plastic lens. (A third, completely redesigned model was made from 1964.) For more information about the Brownie 127 camera, including quotations from my essay above, see Kodak Brownie 127 in Photo-Analogue: Adventures in Analogue Photography by Nicholas Middleton. |